LoRAP-Silpakorn University collaboration:

“Pong Manao Cultural Heritage Promotion/Conservation Project”

November 2002- January 2003

Participation to the project “Pong Manao Cultural Heritage Promotion/Conservation Project”

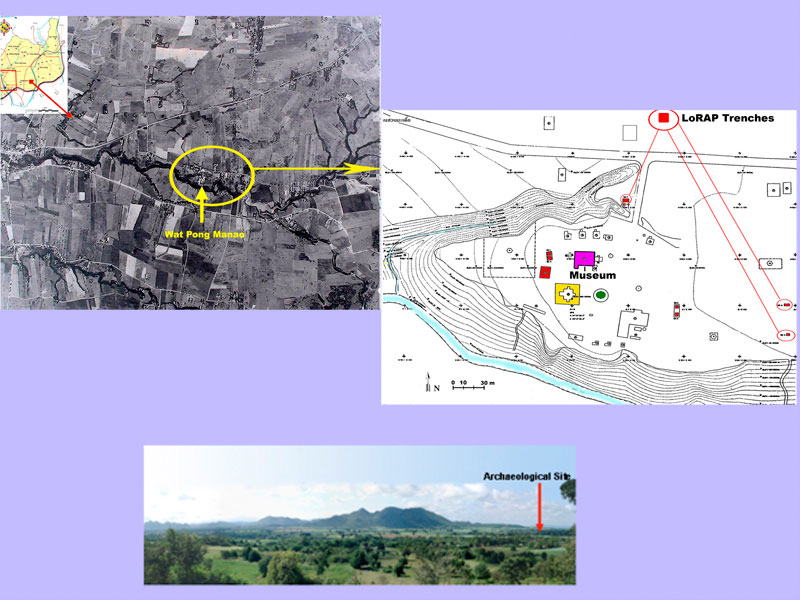

In 2002 the Faculty of Archaeology of the Silpakorn University-Bangkok, in the frame of a MoU with the former Italian Institute for Africa and the Orient (IsIAO), had invited the Italian-Thai LoRAP to participate in the “Pong Manao Cultural Heritage Promotion/Conservation Project”, directed by Surapol Natapintu. The project aimed at the investigation of a then recently discovered archaeological site inside the compound of the temple (Wat) of Pong Manao, a small village in Huai Khun Ram sub-district (Patthana Nikhom District, Lopburi Province). Alongside academic archaeology, the project included an awareness-raising component on Cultural Heritage designed for developing the archaeological site into a local school children self-educating centre and community museum; a challenging project to which we joined with enthusiasm.

The Archaeological Site

The site (14°54’59.13” N; 100°14’48.39” E) is located on a river terrace at the confluence of a natural ditch with a creek ending into the Pasak river, about 10 km to the West [Fig. 1].

In February 2000 the site was subjected to clandestine excavations, promptly interrupted by the local district authorities. In March 2000, the Faculty of Archaeology was required to carry out scientific excavations in order to establish the nature and date of the accidentally discovered burials, the size of the site, and to assist the freshly established “Assembly for the conservation of archaeological sites and natural resources of the Huai Khun Ram sub-district” through a development program of the Ban Pong Manao site in a local education centre and museum. The archaeological investigations carried out from 2001 to 2004 ascertained that the graveyard extended well beyond the looted area. Most graves were richly furnished with vases of burnished red ware, beakers, rings, earrings, bracelets and anklets of bronze, necklaces of carnelian, agate and glass beads, iron tools, bimetallic and iron weapons. As for the date of the graveyard (ca. 6 ha), a time span in the first 500 years CE (late Iron Age) was proposed.

At Pong Manao LoRAP’s specialists investigated (2004) different areas along the presumed limits of the graveyard, with the aim to locate habitation evidences that might be related to the graveyard. Such a task was rather important for us as, in the past, little attention was paid to evidences of habitation activities, often rather poor in comparison to the richness of the graves. Therefore, many aspects of the prehistoric villagers everyday life are little known, e.g. the spatial organization of the settlement.

The LoRAP team investigated three excavation units: Trench 5 and 6 (3 x 2 m, and 2 x 5 m) to the east of the ones where Natapintu had found 13 tightly clustered burials, and Trench 7 (5 x 5,5 m) to the North of the river terrace.

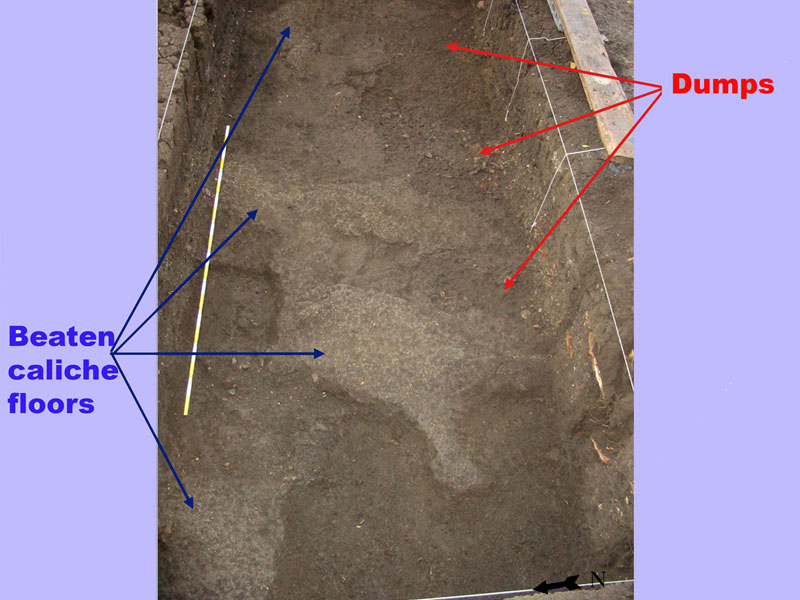

In the Trenches 5-6 two compacted levels of discarded materials (30-50 cm thick) were found, consisting of potshards, fragments of bronze and glass bracelets, handles made of bone/antler, iron tools, fragmented cattle, pig, and deer bones, snails, freshwater fishes and clams. This evidence represent dumps associated to habitation areas contemporary to the graveyard, as suggested by the typology of the pottery shards as well as by fragments of bronze bracelets, finely decorated with concentric circles, spirals and/or nipples motifs, comparable to the entire ones laid in the graves (Fig. 2).

This layer of waste materials has sealed and been cut from several generations of fairly spaced post holes that testify to different stages of houses on stilts (Fig. 3). On the northern edge of the dump in Trench 6 the remains of an infant buried in a large jar were also excavated (Fig. 4). According to the stratigraphic position of the burial and to the typology of the container, it should be considered contemporary to the dump and to the adult burials.

Trench 7. The excavation in a relatively thin deposit (ca. 10 cm) only found few potsherds associated to the foot bones of an individual buried beneath the southern wall of the trench, that we left unexcavated. In Trench 7 (ca. 25 m2) no other burials were found.

As a whole, the data point to a village functionally divided into a residential area along the margins of the terrace, at a close reach of the watercourse, and a graveyard located in the inner part of the terrace. Infant burials were separated from the adults’ graves, as witnessed by the jar burials (one in Trench 5 and two more excavated by Natapintu in Trench 10) associated to habitation remains.

The entire operation of surveying and promoting Ban Pong Manao archaeological site and community museum represents an excellent example of sustainable Cultural Heritage development which produced visible cultural, social and economic fall-out for the rural community in which the site is located (Fig. 5).

The local museum, together with some of the graves left exposed to partially show the prehistoric necropolis, have become a pole of tourist attraction at a regional and inter-regional level. The museum, which in 2005 had about 14,000 visitors, has become an educational centre for schools of all kinds in the Patthana Nikhom district, also thanks to the well-trained local guides and some well-constructed multimedia. Furthermore, the attached small shop for the sale of local handicrafts is an additional incentive for the local community to take care of the museum itself (Fig.6).

Although on a small scale, LoRAP contribution offered to this little but exceptional example of sustainable Cultural Heritage development has been fully rewarded. As it has been the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, thanks to which LoRAP had the opportunity to stress the relevance of the prehistoric sites protection for the cultural and economic development of local communities (Fig.s 7-9).