Research area, research aims and objectives fulfilled:

a Brief Summary of 32 Years of Activities

Erica Fatland*

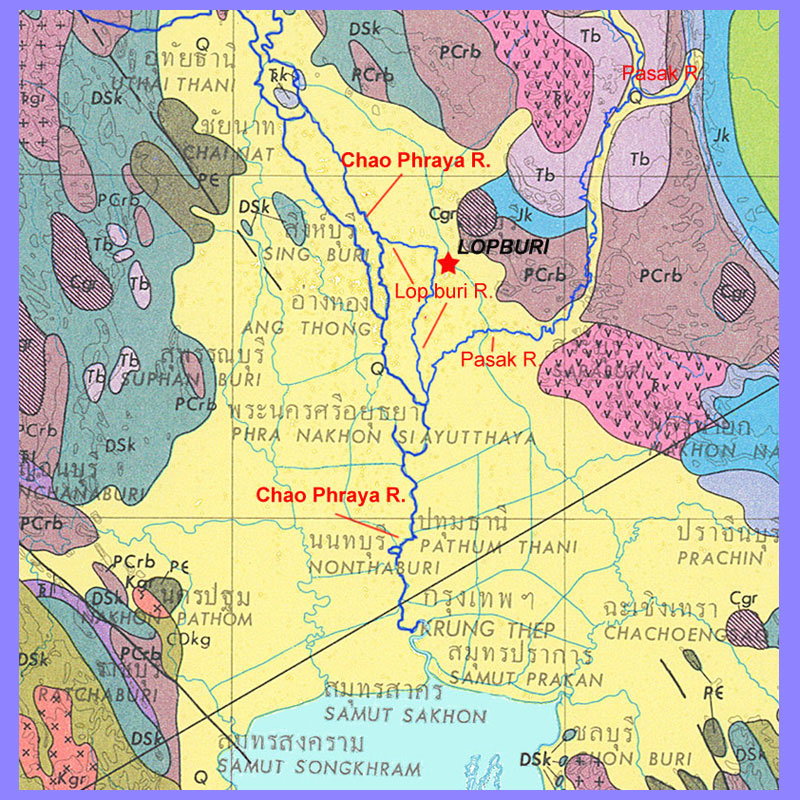

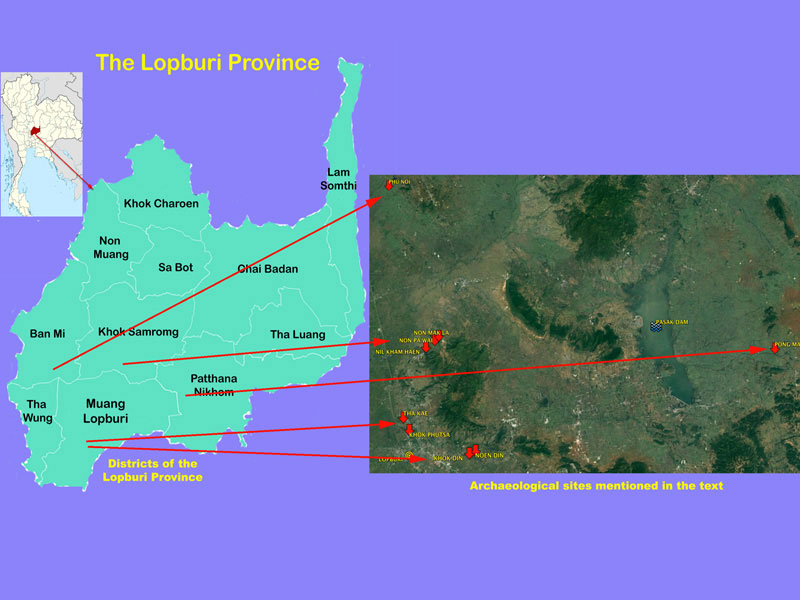

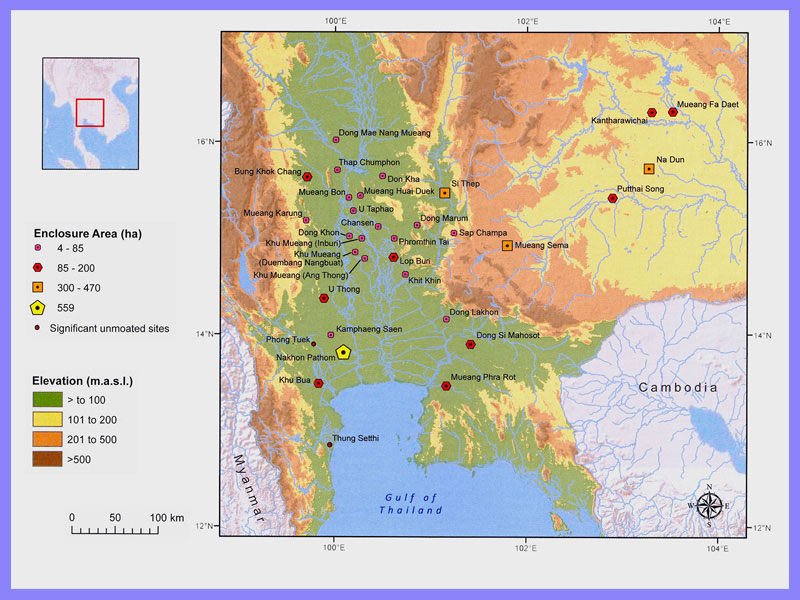

- The LoRAP research area is the Lopburi Province (mean altitude 15 m. asl), so called after the main historic city of the region. The Lopburi River (95 km long), a branch of the Chao Phraya River, and the Pa Sak River (513 km N-S) eastern tributary of the Chao Phraya, drain the Lopburi Province (Fig.s 1-2). The alluvial plains of the Lopburi and Pasak make up the eastern edge of the tectonic depression known as the Central Plain (ca. 500 km NS x 100 km EW), cut from North to South by the Chao Phraya, main water course of Thailand. This region enjoys a tropical savannah climate (m.a.temperature 28.6 °C) with a rainfall of 1370 mm concentrated in the wet season (May-October). The physiography of the Lopburi province includes the Holocenenic alluvium of the Lopburi Plain (LP), dotted by isolated formations of residual rocks (known as inselbergs), and, to the east-northeast, the mountain chains of the Petchabun-Dong Phaya Yen range.

- These reliefs, originating from the friction between the Shan-Thai, Indochinese, and Pacific continental plates, consist of Carboniferous-Permian limestone-and-sandstones and of late Tertiary intrusive rocks; upon contact between the two lithological horizons, the copper mineralizations exploited in antiquity emerge ( 3).

- The project aims to define the role played by the emergence and expansion of agriculture (mainly millet and rice), by the growth of craft activities, and by long-distance trade in the endogenous processes that led to the formation of local complex societies, including the role played by interactions with Chinese and Indian civilizations, between ca. 2000 BCE and 1000 CE.

- Over a period of 32 years of field activities in the Lopburi province, the Project carried out excavations at Tha Kae (Lopburi Capital District), at Phu Noi (Ban Mi District), at Khok Din and Noen Din (Lopburi Capital District), and at Khok Phutsa (Thanon Yai District). At the invitation of the Department of Archeology-Silpakorn University, the project collaborated in the investigation of the Ban Pong Ma Nao site (Patthana Nikhom District), and collaborated in the excavations of the Thai-American “Thailand Archaeometallurgy Project” (TAP) at the sites of Non Pa Wai, Nil Kham Haeng and Non Mak La (Khok Samrong District) (Fig. 4).

Several field seasons have been devoted to the study and restoration of the excavated materials stored in the King Narai Palace National Museum and in the 4th Regional Office of the Thai FAD in Lopburi.

- LoRAP’s investigations were also accompanied by archaeological and geomorphological surveys that, although limited by the shortage of funds, led to the identification of several pre- and protohistoric sites, as well as to a better understanding of man-environment relationships over a period of three millennia ( 5-6).

Much of the project objectives have been achieved; in particular, it has contributed to establish a regional chronological sequence that, valid for the entire central Thailand, harmonizes with the cultural sequences accepted for the whole Mainland Southeast Asia.

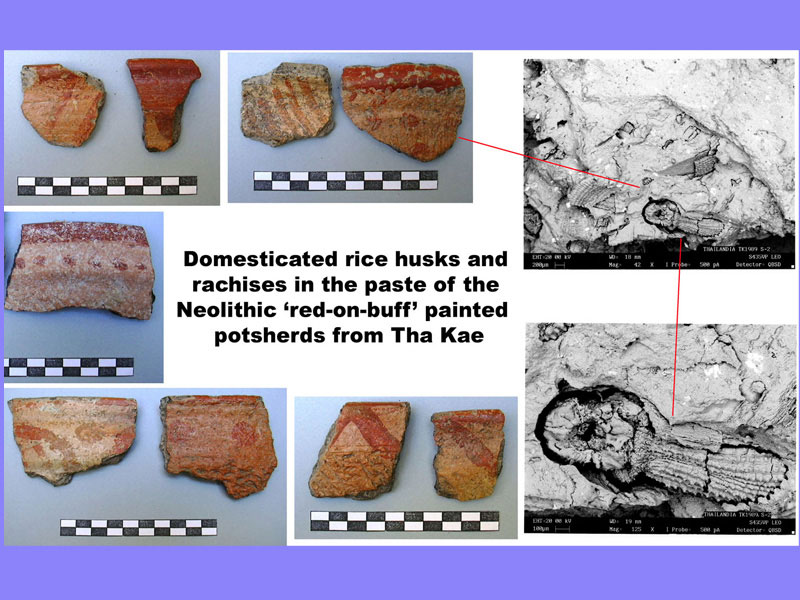

- The emergence of millet/rice cultivation in the region (early 2nd millennium BCE) has been framed in the multi-faceted, and complex phenomenon of agricultural dispersion, began in the 4th millennium BCE in the middle valley of the Changjiang river in China. In the span of two millennia, knowledge for the management of agricultural practices filtered through the dense network of small and large river valleys of southern China until it reached, in patches, the hunter-gatherer societies of Mainland Southeast Asia ( 7).

- In the 2nd millennium BCE, the early peasant communities who had settled on the river terraces in the internal marshy environments of the Gulf of Thailand, which at the time lapped the Lopburi Plain, started the first changes to the natural landscape of the LP.

- At the end of the 2nd millennium BCE copper metallurgy emerged in Central Thailand, in consequence of a southward technological diaspora, start from the Changjiang valley, approximately through the same routes of the older agricultural dispersal. The emergence of copper metallurgy induced intense deforestation along the slopes of the mountains and hills due to the increased extraction of copper (and later iron) ores, and to the need of fuel for smelting ores, in association with the slow expansion of agricultural activities into new land taken from the forest.

- The growth of craft activities, including copper metallurgy, documented at several sites of the LP in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE, was one of the variables of a wider process of social complexity growth triggered by the expansion of agricultural production, the availability of natural resources and, from around 500 BCE, by iron metallurgy. In this process the early contacts with China and India, of which in LoRAP’s excavations was found the tangible evidence, played a strategic role.

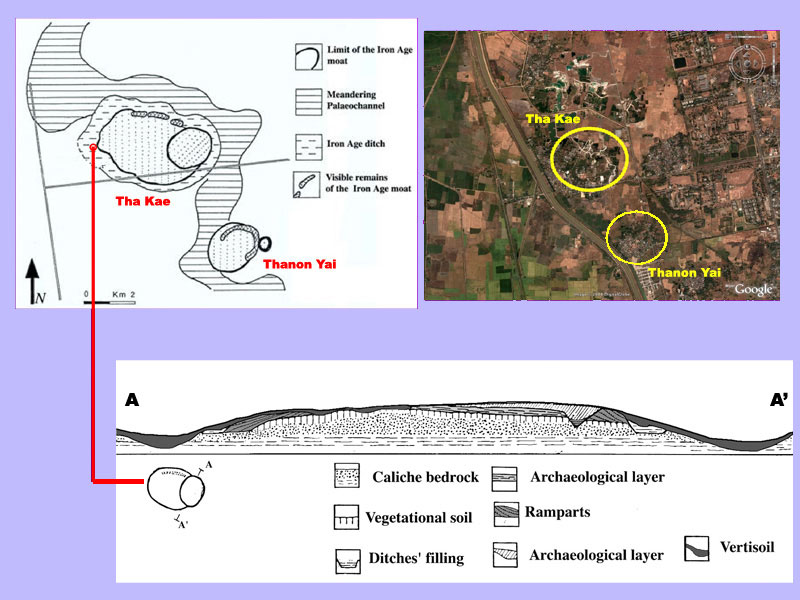

- In conjunction with a phase of drier climate occurred at the very end of the 1st millennium BCE and the beginning of the following one, the human environment of the LP saw a process of substantial social and economic change with the emergence of centres of social aggregation, the ‘moated sites’ (e.g., Tha Kae) (Fig. 8-9), associated to technological innovations, epitomized by the iron tools and the paddy fields of Chinese inspiration.

Fig. 8 – 1945 aerial photograph (William-Hunt Collection) of the area to the north-east of Lopburi with the silhouettes of three intact moated sites (the northernmost of which is Tha Kae).

- Such a growth was also supported by the continued interaction with the non-Han polities of Southwest and Southeast China, as well as by the initial interaction with the Indian Subcontinent (3rd BCE-2nd cent. CE) traceable in the imports and local imitations of “Indian luxuries”.

- The control and management on the long-distance exchange circuits by local elites were strategic for the formation of state-like polities, definitely based on the adoption and adaptation of Hindu-Buddhist ideological concepts and forms of worship (proto-Dvaravati period ca. 3rd/4thto 6th cent.).

- The growth of social complexity is reflected in the blossoming of the Dvaravati city-states and of the Dvaravati artistic phenomenon (6th–13th century) that spread all over Central Thailand and beyond in a network of ports, urban and religious centres of Mon language and population (Fig. 10).